Photos: Sergio Mendoza

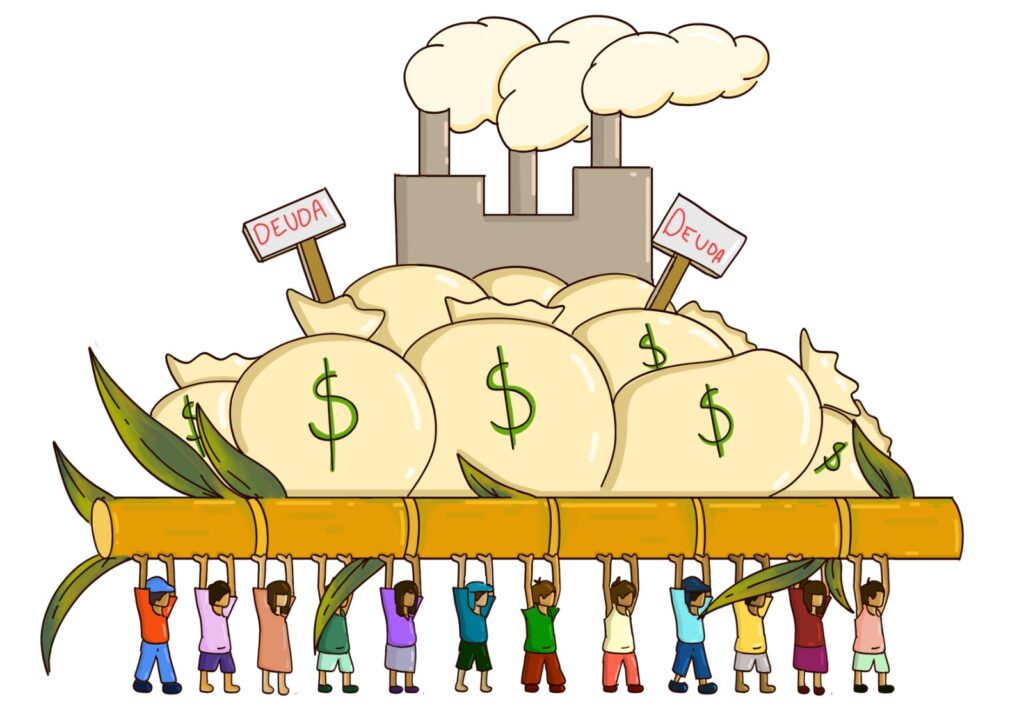

«The sugar mill is a big hoax,» says a man who overheard my conversation with an official of the Mayor’s Office of San Buenaventura, in La Paz north. It is late afternoon on a Thursday in November 2023 and we are enveloped in a cloud of smoke, with an unbearable heat due to the fires that are consuming the Bolivian Amazon. The man is native of the area, asks me to keep his name confidential and tells me that the state-owned San Buenaventura Sugar Company (EASBA, for its English acronyms) convinced the communities to clear their forests and grow sugar cane with the promise of economic development. The indigenous people accepted, but since everything was done with company equipment, «in the end they got the bill and the brothers ended up with debts of millions of Bolivianos».

This is a reality confirmed by a dozen sources, including sugarcane growers, authorities and public officials with whom I spoke. Indigenous people who had never taken out a loan before are now indebted to the public company for the deforestation of their territory and the cultivation of sugarcane. The communities that accepted the deal receive 20% of the production value, while the remaining 80% goes to pay their debt.

The problem is that production is lower with each passing year, so there is less value to honor these commitments. Initially it was estimated that the debt would be paid in five years, but in that time the cane growers must acquire more credit to buy pesticides, seeds and other inputs.

«We had planned to pay the debt in five years, but as there are deficiencies in production, when it is time to harvest, the issue of fertilizers and certain things comes in, and then it is another acquisition of debt,» says a sugarcane grower from the Altamarani community, the closest to the mill, whose name is withheld for fear of reprisals.

Jorge Canamari, president of the Indigenous Council of the Tacana People (CIPTA), a native group at the Bolivian Amazon, rides in a dark blue vehicle. He travels through landscapes that look more like the altiplano than a rainforest, with dry, ochre vegetation. Around the road, fiery flames consume life and columns of smoke rise into the gray sky. In the face of the authorities’ inattention, he moves in this car with his family, and a plucked parrot dying of thirst, to help the communities besieged by the fires. In the midst of these burdensome labors he makes time to talk about the sugar mill.

«There are communities in debt with more than Bs 4 million and in five harvests not even half of it has been paid, because production is decreasing every year. It is unfortunate,» he says.

Neither EASBA nor the Ministry of Productive Development and Plural Economy, the ministry in charge of the area, provided information requested for this report.

An unprofitable company

In addition to the debts of the local communities, the public company itself has debts with the Central Bank of Bolivia (BCB) for US$ 265 million, money that was given to the company for its creation and for the construction of the sugar mill. So far the loan has not been repaid, according to reports from the monetary entity. The company’s income does not cover its expenses due to deficient sugar cane and sugar production, so it must constantly seek state support, says Daniel Robison, a soil conservation specialist who has thoroughly investigated the issue.

«I myself have tried to produce sugarcane and I know the limitations. I have my trapiche rotting there,» says the «gringo» looking man from La Paz, 63 years old and almost 30 years living in Rurrenabaque, Beni, where he decided to set up his home with his late wife. Now he lives with «Jucu», an affectionate dog that follows him everywhere around his house, located a few blocks from the main square, and with a cat that hunts mice.

Robison explains that the intention to grow sugarcane in San Buenaventura is part of the so-called «March to the North», an emulation of the «March to the East», which between the 40’s and 50’s took place with the construction of sugar mills in Santa Cruz. Until then, the department of Santa Cruz had been a neglected region, which had to be connected by roads to the highlands where economic activity was booming thanks to mining and government bureaucracy. A similar destiny is intended for the Bolivian north; but the differences between these regions are not considered.

«There are people who, more than loving La Paz, envy Santa Cruz. They are unaware of the differences and underestimate what is here. They don’t care one bit about the resources in the north of La Paz, where there is a beautiful Amazon forest. And they don’t give a damn!» says Robison, with rage and impotence. «The forest, for them, is something they have to take out to plant sugarcane or African palm. That is a total colonized mentality!»

There were years when EASBA could not even cover its current expenses. In 2018 current expenses reached Bs 128 million, but revenues only Bs 34 million. For 2023 revenues were projected at Bs 62 million, although programmed expenses are unknown. At the time of publishing this story, neither the state-owned company nor the area ministry responded to queries about its financial statements.

Amazon forests disappear

It is mid-November 2023, the communities around the sugar mill are burning and drowning in smoke. The indigenous people are desperate. They run from one side to the other with the little water they have left. The drought has hit them for four months in a row. The forest fires have put them through hell.

Standing behind a house in the community of Buena Vista, agronomist Marco Patiño watches as the fire sprouts from under ashes scattered on the ground and rants against the government’s plans. Yesterday the flames engulfed a house in this village and partially burned at least four others.

«With the discourse that we are autonomous producers these disasters originate, the forest is being cleared, and now these are the consequences. Since the 70’s it was already known that the sugar mill was not going to work. If this is the model that our government is promoting, the indigenous people are going to have to migrate to other places,» says Patiño, while a 10-year-old boy runs with a backpack loaded with water to spark the flames that seem to come out of the underworld.

By 2021, approximately 4,500 hectares (ha) of forest had been deforested to grow sugarcane in San Buenaventura. In reality, deforestation was expected to be greater. The mill needs about 14,400 hectares to operate at 100 percent of its capacity; it is currently operating at only 30 percent. The high cost of clearing the forest and the low profitability of production were somewhat in favor of forest conservation. But plans to continue cutting down trees remain in place.

The sugar mill is an amalgam of metal equipment installed in front of a concrete block where EASBA’s offices are located: three levels with enough space for 400 cubicles, but several of them look abandoned. Workers report that typically up to 60 people work on maintenance tasks, and during the harvest season the number of workers triples.

Internal sources reported that one of the main problems is that the mill’s technology is third-rate Chinese, so wear and tear is rapid and spare parts are hard to come by.

Although the company EASBA was founded in 2010, the mill began construction in September 2012 by the Chinese company CAMC at the direct invitation of the government of Evo Morales, at a cost of US$ 175 million. The money came from the BCB loan. The contract was not made public, it does not appear among the documents of the State Contracting System (Sicoes) and was not provided by the authorities at the request of this report.

Around the sugar mill and the blue office building there are extensive sugar crops divided by trees left as windbreaks, parched by drought and sun. In a few more days this place, which is already full of smoke, will be hit by the fire, which will consume up to 150 hectares of the plantations. For now the workers are on alert, as are the nearby communities. The closest is Altamarani, a village on the edge of the Beni River that can only be reached by car through the road opened by EASBA.

The community used to be in the middle of the bush, surrounded by gigantic trees that were cut down to plant sugar cane. They used to draw water from the river and nearby streams, but now they are contaminated by waste from the mill and all the human activity further south. They now rely on a low-pressure well that is failing.

«Deforestation has been intense. It has affected the drought. But there are also rare diseases that have appeared. There are no doctors here and we save ourselves with natural medicine and the Yatiri,» Gilmer Cartagena Chao, corregidor of the community, tells me. «The corn has dried up, the yucca has rotted, the cocoa has gone bad, and the bananas are getting thinner and thinner.»

Although the sugar mill is just a few steps away, people have to migrate in search of work, says Gilmer and agrees with him Roxana Añez, a 52-year-old Beni woman who settled here when she was 16 pursuing love. She tells me that men can harvest sugarcane, but there is no room for them in the mill, only for professionals.

She glances around through the empty windows of the blue-painted village house and says: «We have suffered the most damage. Look at the deforestation we are suffering. We don’t know where the fire is coming from, whether it will come from the cane fields or from somewhere else, but we feel it.»

Añez tells me that in the past the people lived off their crops, hunting and fishing; but now their crops are drying up, the fish are depleted in an increasingly sick river, and the animals are fleeing because their habitat has disappeared. «EASBA has cleared land to make their sugar cane fields and we have no forest, and with this fire we are going to be left with nothing,» she sighs.

Neither the government of La Paz, nor the Ministry of the Environment, nor EASBA responded to queries about the environmental impact studies, licenses and other studies that would have been carried out for the installation and operation of the sugar mill.

Bitter sugar

«The news was sweet,» says Dario Mamio, the corregidor of Bella Altura, another small community of San Buenaventura, in the middle of the dense grove. «Near us is EASBA, the pests are evolving because of the agrochemicals they spray, and our traditional crops are affected. They pollute our streams and the river during harvest time. The fish die and there is no compensation».

Sugar production generates environmentally polluting waste, such as bagasse, cachaza, and vinasse. Sources close to EASBA pointed out that the waste is not adequately treated. In small quantities, vinasse works as fertilizer, but in large quantities it is a poison for vegetation. Better-prepared mills have irrigation systems to spread the vinasse on their crops; but EASBA deposits most of it in artificial pools that could leak and cause damage to the ecosystem, they said.

I ask soil expert Daniel Robison how he sees the future of San Buenaventura and sugar production. His answer is not encouraging. Cooked by the unbelievable heat and enveloped in the smoke, the academic in love with the Amazon tells me that never before in recent history had temperatures reached as high as now in this region: over 40 degrees for several continuous days. That it had never stopped raining for four months in a row. Never before had the jungle burned as it has in recent years. The fire, usually started in the farmlands, was extinguished when it reached the rainforest; but that no longer happens. The forest is dry and the fire has penetrated it, and next year it will be easier for it to burn.

«The government insists on taking out the forest and putting in sugarcane, African palm, or whatever. They haven’t made any effort to see how to take advantage of the resources that do exist. Now that this has been burned, it will be easier to clear the land,» says Robison.

I put the same question to Roxana Añez, the Altamarani woman who migrated here when she was 16 to start a family. Her answer is firm, but demoralizing.

«We have said that they can take us out dead, but we are not going to leave our land as long as we stay alive».